I am travelling again and in less than a few hours, I will be on the other side of the Rhine. Berlin. And this time, I am attending the Berlin Energy Transition Dialogue as a press delegate. While preparing my trip, I am also reflecting on a journey deeply connected with energy narratives. Growing up in Kolkata, India, « load shedding » was a regular part of life, a term synonymous not just with power cuts, but with the broader struggles of industrial decline. This experience was not just about the inconvenience of power outages, but rather a deeper narrative of economic shifts.

Back then in the nineties and the early years of 2000, Kolkata, under a specific regime, faced numerous strikes and unemployment, evidence to the need to balance power distribution and industrial demands. The irony lies in today’s Kolkata, where load shedding is a thing of the past, not due to a grand energy transition, but rather an absence of industrial demand, leading to an almost overflowing electricity supply. This personal backdrop forms a stark contrast to the energy landscapes I encountered later in my career, especially at international forums like COP21 in Paris.

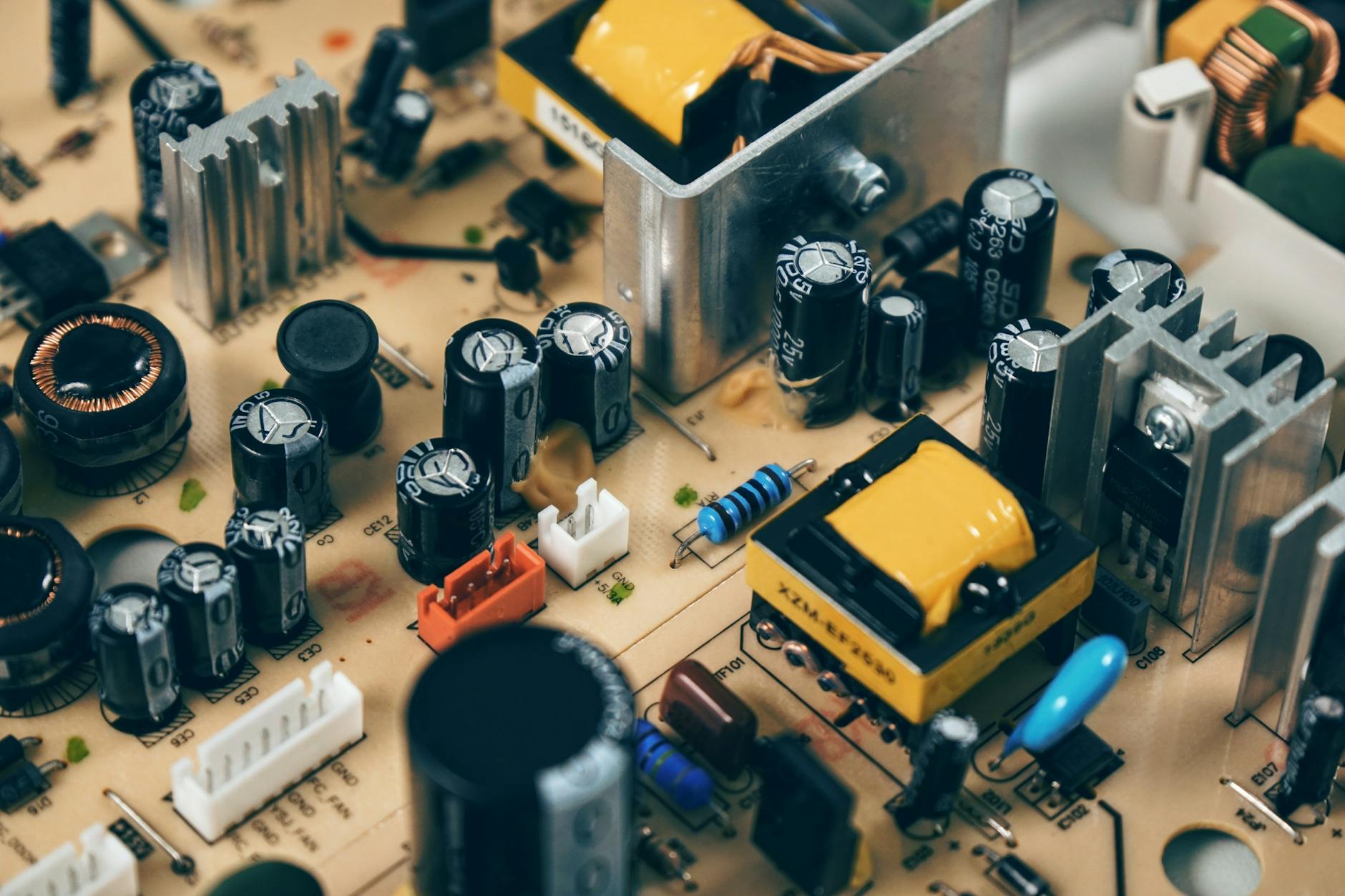

Photo: Writtwik

I had the modest opportunity to be part of the media team for the Embassy of India, allowing me to study countless documents over a week. While everyone buzzed about India and France as key players at Le Bourget, deep inside, I was riddled with questions.

Admittedly, like most people, climate issues hadn’t deeply intrigued me beyond my 2009 master’s dissertation in Earth Sciences at the University of Paris-Cité (Diderot). It was during my time translating in the media center at COP21 that I found a burning desire to understand climate stakes more deeply.

I pondered: What are the tangible effects of climate change? Is there an effective climate policy? What is the science behind it? How can green activists convince decision-makers to implement coherent policies? Is there a ‘jugaad’ (an innovative fix) for all these questions? Probably not.

These questions haunted me for some time, compelling me to focus on the topic of energy, an area where I lacked expertise. The first thing that came to my mind was light, a resource still inaccessible to much of India. Light leads to energy. How is energy utilized in an emerging and ambitious economy like India?

Searching for organizations working in this field, I stumbled upon TERI (The Energy and Resources Institute) in New Delhi. Though I had heard of this NGO during COP21, the lack of French media coverage made it challenging to research them further. My discovery of TERI marked the beginning of a new chapter in my journey towards understanding and advocating for energy solutions.

While aiding The Energy Research Institute to disseminate its ‘lighting a billion lives’ project across francophone nations, a deep-seated emotional bond with energy advocacy burgeoned within me. This advocacy journey seamlessly intertwined with fate at the Paris Peace Forum in 2018, where I crossed paths with Dr. Asif Iqbal from the Indian Economic Trade Organisation. Our bond, cemented by shared aspirations of fostering cross-country connections, has flourished. While Asif navigates tangible trade dialogues, my role meanders through the promotion of intangible cultural heritage, leading us to a common confluence – the estuary of mutual understanding and cooperative goals. Our collaboration, underpinned by a shared pursuit of a greener future, makes the forthcoming dialogue an exciting convergence of ideas and insights.

Photo: Asif, at the Energy Panel of the European Parliament

This inaugural article for the Berlin Energy Transition Dialogue is, therefore, much more than a discussion on energy; it’s a story of how Dr. Asif Iqbal orchestrates dialogues and creates synergy across various domains. Therefore, keeping in line with the theme of the Berlin Dialogue, I’ve prepared four tailored questions to explore these dynamics. These questions aim to focus on how the Indian Economic Trade Organisation is influencing policies and industry standards in semiconductor manufacturing, especially regarding renewable energy integration. They also touch upon eco-friendly practices within the semiconductor industry, global collaborations for technological advances in this sector, and how geopolitical tensions are maneuvered. Through these questions, I would like to shed light on the multifaceted role that Dr. Iqbal plays in bridging gaps and fostering partnerships across the globe.

Writtwik: As a key player in lobbying, how is the Indian Economic Trade Organisation influencing policy and industry standards to promote the integration of renewable energy in semiconductor manufacturing? Are there specific initiatives or recommendations you’re championing to encourage sustainable energy infrastructure in this sector?

Asif: The Indian Economic Trade Organization (IETO) operates as a facilitator of economic collaborations, plays a crucial role in driving sustainable initiatives within the semiconductor sector and more. We act as a bridge between Indian semiconductor manufacturers and global entities specializing in green energy solutions. Through collaborations, IETO facilitates the exchange of technologies and best practices, fostering the adoption of eco-friendly manufacturing processes. Moreover, IETO contributes to the upliftment of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) within the semiconductor industry, ensuring that sustainability measures are inclusive. The organization conducts capacity-building programs, provides financial support, and facilitates technology transfer to empower SMEs in embracing sustainable practices.

In tandem with India’s broader vision, IETO actively engages in policy advocacy, working closely with governmental bodies to promote regulations that incentivize the use of sustainable energy sources in semiconductor manufacturing. The organization also advocates for and supports research and development initiatives, encouraging innovative technologies that contribute to energy-efficient processes.

Furthermore, IETO creates networking opportunities for SMEs, fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing on sustainable practices within the semiconductor industry. The organization also establishes recognition programs to acknowledge and incentivize companies, particularly SMEs, excelling in sustainable energy adoption.

Through these combined efforts, India, with the proactive involvement from large enterprises, strategic International collaborations, boost from the SME’s, positions itself as a global leader in driving sustainability within the semiconductor industry. The collaborative approach not only aligns with international environmental goals but also strengthens India’s semiconductor ecosystem by promoting inclusive and resilient practices.

Writtwik: What incentives or policies are being advocated to promote energy-efficient practices within India’s semiconductor industry, and are there any specific programmes encouraging the adoption of such technologies?

Asif: In India, the government has historically introduced various initiatives to promote energy efficiency and sustainability across industries, but specific programmes for the semiconductor sector may vary. Policies related to renewable energy adoption, energy-efficient technologies, and environmental sustainability can have indirect effects on semiconductor manufacturing.

The Indian government has set up the India Semiconductor Mission (« ISM ») to tackle the worldwide shortage of semiconductors and encourage manufacturers to establish their semiconductor facilities in India. Under the ISM, the government has introduced four schemes. As the central agency, ISM will assess the technical and financial aspects of received applications, suggest the selection of applicants, and undertake other responsibilities assigned by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology as needed.

With India’s Finance Minister, Ms. Nirmala Sitharaman at the Huddle Conference in Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

The Ministry of Electronics and Information (MeitY) is looking for applications from 100 Indian companies, startups, and small businesses for its Design Linked Incentive (DLI) Scheme. This program has three parts: support for chip design infrastructure, incentives for product design, and incentives for deployment. C-DAC (Centre for Development of Advanced Computing), a scientific society under MeitY, will be in charge of making sure the DLI scheme works. The main aim of the DLI scheme is to help at least 20 Indian companies that work on designing computer chips. The goal is to help these companies make more than INR 15 billion or 167 million euros in the next five year.

Writtwik: Can you shed light on how the organisation is facilitating collaborations between Indian semiconductor industry and global leaders in renewable energy, and any significant partnerships aimed at propelling India towards a sustainable semiconductor future?

Asif: With India excelling in chip design, the recently authorized facilities will drive the advancement of chip fabrication capabilities, fostering the growth of indigenous packaging technology. This transformation is anticipated to generate fresh employment opportunities and simultaneously increase semiconductor production capacity. According to the central government’s projections, the establishment of three new units will directly impact 20,000 high-tech positions and indirectly lead to the creation of an additional 60,000 jobs.

The Indian semiconductor industry has gained significant investments and commitments from top global chip manufacturers, showcasing confidence in India’s potential as a semiconductor hub. Notable contributions include Micron’s INR 22,500 crore semiconductor facility in Gujarat, Foxconn’s USD 1.2 billion investment for electronic components manufacturing in Tamil Nadu, AMD’s USD 400 million investment in Bangalore for the world’s largest R&D facility, and Applied Materials’ USD 400 million investment in Bengaluru for semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Additionally, collaborations with industry suppliers, discussions with global players, and a memorandum of cooperation with Japan further highlight India’s emergence in the semiconductor sector. Sahasra Semiconductors has already established a production unit in Rajasthan, set to commence production of locally-made memory chips in October 2023. We at the IETO strongly highlight the need for a collaborative effort between the Indian government, industry, and global players to establish resilient semiconductor supply chains worldwide.

Writtwik: With the global semiconductor industry often at the center of geopolitical tensions, particularly between major powers like the US and China, how is the India Economic Trade Organisation navigating these complex dynamics? What is India’s strategy to maintain its growth and independence in this high-stakes environment while balancing international relations?

Asif: India’s role in the geopolitical landscape is underscored as it emerges as a significant player in the semiconductor industry. While the primary focus of the discussion revolves around global dynamics, tensions between major powers, and strategic initiatives, India’s proactive involvement is evident. The extended summary previously mentioned India’s efforts in attracting substantial investments from top chip manufacturers, such as Micron, Foxconn, AMD, and Applied Materials, reflecting the country’s commitment to developing a robust semiconductor ecosystem.

These investments, I am convinced, position India as a major player in the global semiconductor supply chain, contributing to the geopolitical equation. The Memorandum of Cooperation signed with Japan further emphasizes India’s strategic collaborations to bolster the semiconductor sector. Amidst the intensifying competition between major nations, India’s growing semiconductor capabilities add a unique dimension to the geopolitical narrative, enhancing its role in the intricate balance of power in the technology and semiconductor domain.

Currently, IETO plays a vital role in driving economic partnerships, especially in the semiconductor sector. It actively engages in promoting investments, trade deals, and partnerships, significantly contributing to building a strong, global semiconductor supply chain network. This approach, which prioritizes collaboration and shared economic gains, aligns with a strategy that combines diplomatic and business perspectives, skillfully managing geopolitical complexities without direct involvement.

Writtwik: Thank you so much, Asif. Really appreciate it.

Acknowledgements:

Dr.Asif Iqbal, President, Indian Economic Trade Organisation